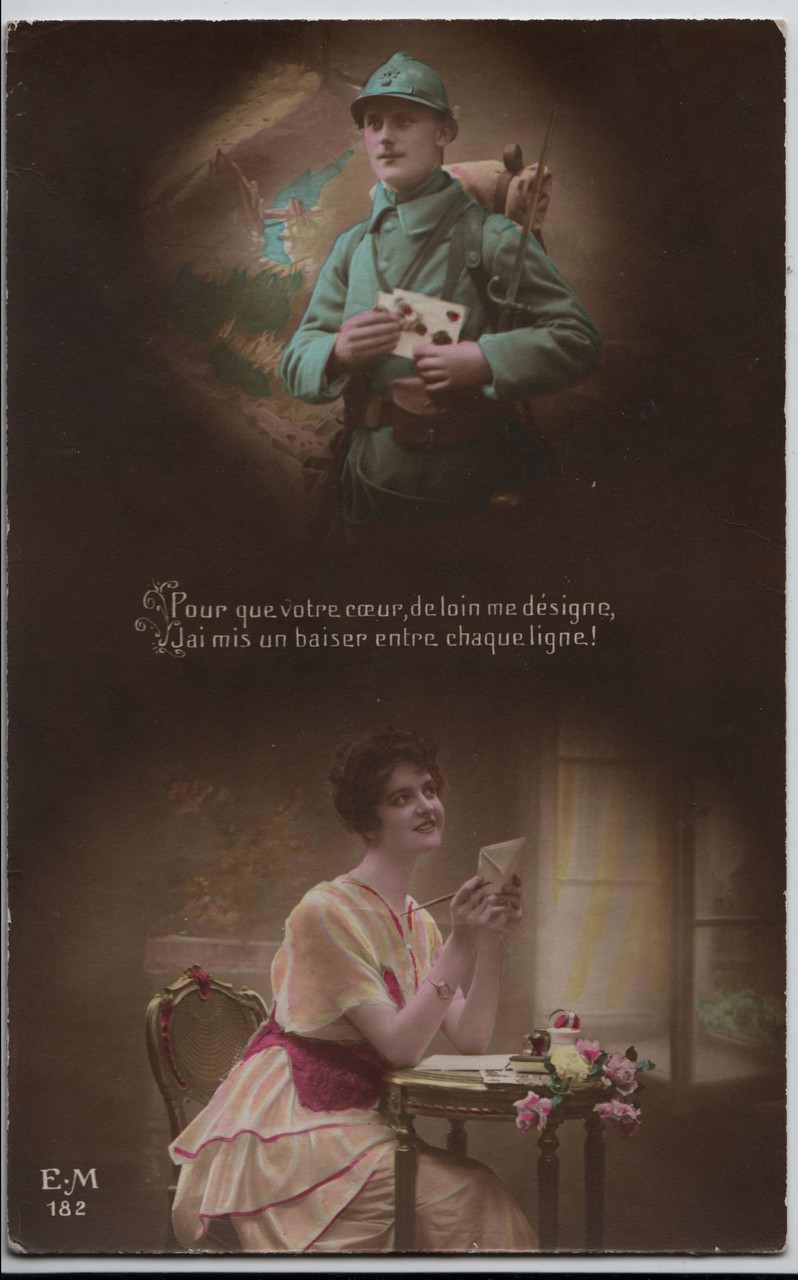

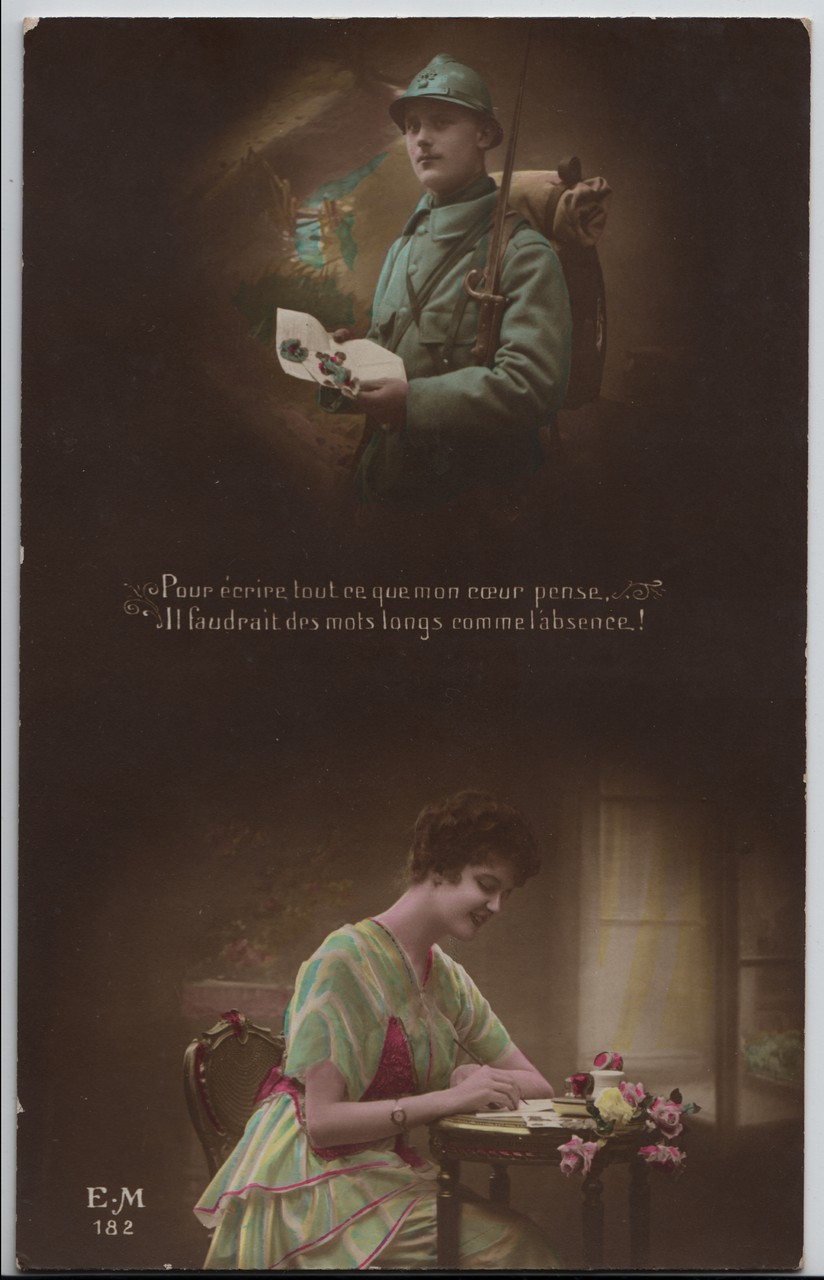

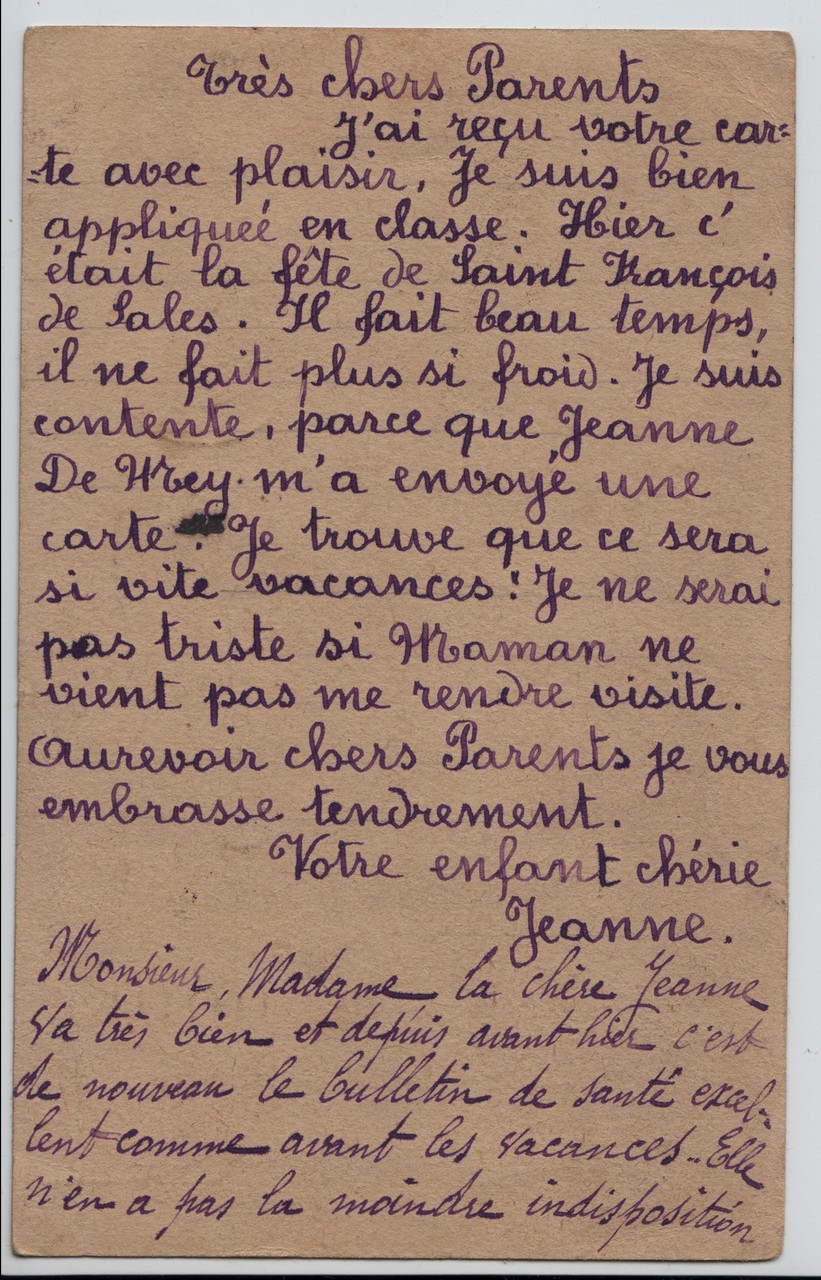

French and Belgian postcards 1

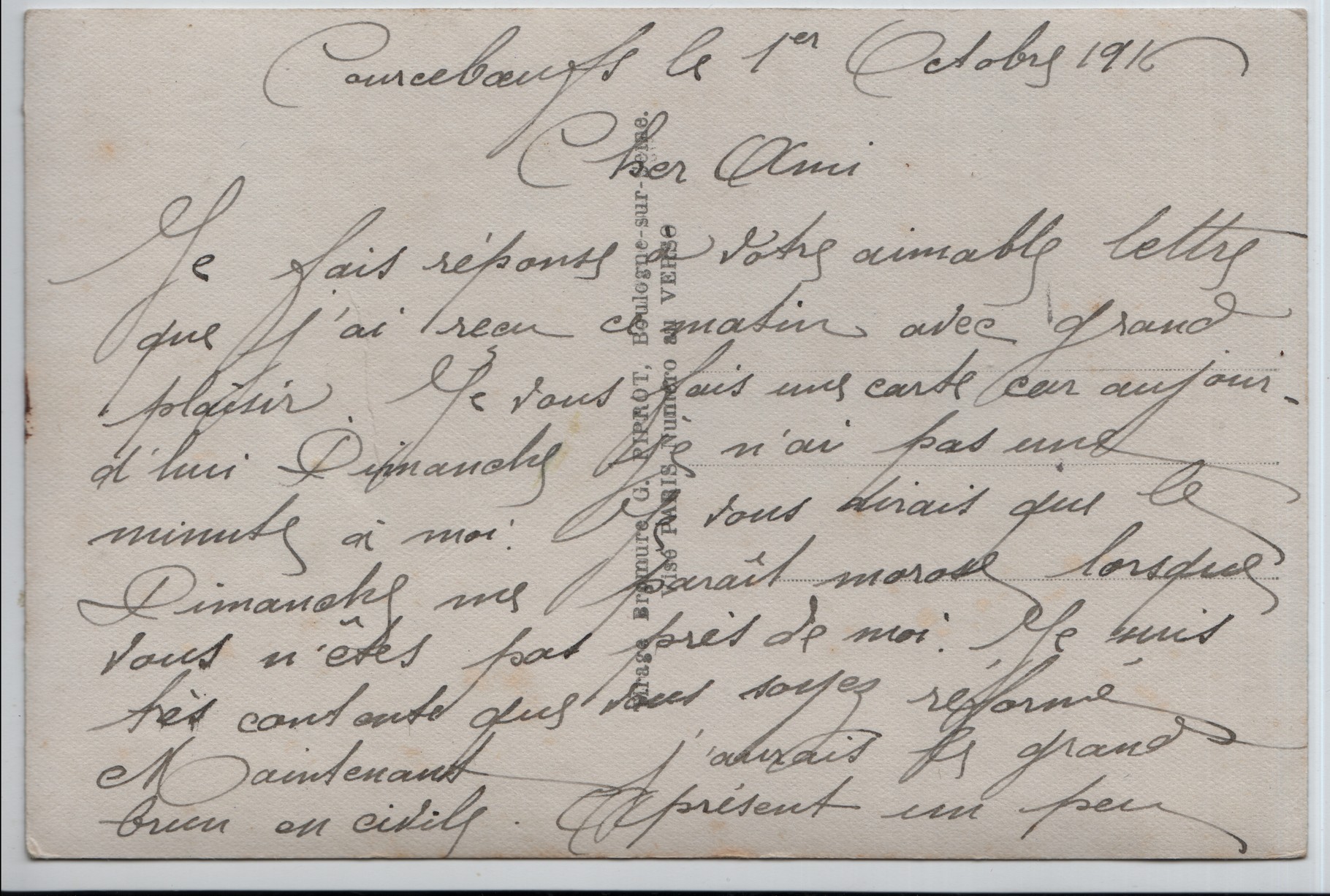

Postcards 1 & 2: 1st October 1916

Dear friend

I answer your kind letter that I have received this morning with great pleasure. I am sending you a postcard because today Sunday I do not have a minute to myself. Let me tell you that Sunday seems morose when you are not next to me. I am very happy that you have been declared unfit for service and now I will have the big brown haired guy in civilian. And now a bit of manners. This won’t be military life. I trust that you will be good. You know yesterday evening you gave me a fright. I was told that you were not convalescent. So you think when I saw your letter I was happy. I will write a long letter tomorrow. The family is fine.

Receive dear friend my sweet souvenirs, my good kisses - from your friend who loves you. Yvonne Perot.

Note: Courceboeufs is in France in the department of Sarthe, south west of Paris, just above Le Mans.

Unfit for service: this is a translation of the French term “réformé”. “Etre réformé” meant to be sent home usually on medical grounds. This was happy news for families.

“A present un peu de chiquet”: colloquialism - chiquet is possibly chiqué - which means manners. Yvonne is possibly warning her boyfriend that, when he gets back to civilian life, he will have to smarten up and show good manners. Life in the army was very different from civilian life and she might be worried that he has forgotten how to behave like a gentleman or even how to groom himself properly. The poilus had a hard life: not much time for good manners and not many opportunities to stay clean and well groomed (i.e. shaving, cleaning, dressing well in clean clothes- all things that are especially important to please the ladies!).

“Je pense vous serez gentil”: literally “I think you will be kind”- Yvonne is possibly expressing her confidence that everything will be fine and that she will get back the same man as the one who left to go to war.

Postcard 4: 16.7.1917

Could you send me a sample with price of your dog biscuits - bulk and retail - and also poultry feed?

Mr Pardon

Rue de Namur 37

Sincerely

Postcard 8: 25th October 1915

I got your letter of the 22 my little darling. Keep writing to me at the 11th [sector]. It is the vaguemestre of our battery that gives me the letters I receive. For those I send I could also give them to him but if I leave them at the office where I work, which I am not entitled to do, it is one day quicker. So, this letter will leave tonight at 4pm from where I am writing it, instead of, with the vaguemestre, I would have had to give it to him yesterday or this morning before 7am at the latest. So that’s good. For my trench coat it’s another matter. It’s lucky that I can wait - especially here. Figure it out, the packet is in Briançon and it will arrive here at the first opportunity. The administration, that Europe envies us for, has planned that out! Your poor apples! I would have been better off leaving my trench coat at the fort rather than sending it back to you at the beginning of the summer. I think that for the next parcel you need to send me by other means than the post office, you will need to do the same as Chapolard does, which is to address the parcels to a bicycle shop in Verdun. I have sent yesterday for Jeanjean a box of dragées. It is his feast day on the 28th. Then I went to have a bath. That reminded me of the death of Jacques. It was when I was waiting for my turn in the antechamber of the establishment that I read mum’s letter announcing me the catastrophe. Yes, Mimi must have a very sad and hard time. Was Alexandre in Champagne? How many died there? It must be terrible. There was a terrible mess just when we were about to make an advance.

I have received a letter from Jean. He must have left Champagne as they have been travelling for 24 hours by rail. I understand that he is somewhere near Alsace, but his sector number has not changed.

What did the Pollosson told you? Concerning your thoughts inspired by the sermon AE Schimann, they are right. At the moment no middle position, either fanatic or fatalist. No space for anything else.

Change of weather since yesterday evening: warming up of temperature since yesterday evening and rain. We can appreciate now being in a dry place, in barracks, and me who spends all my time in an office!

And now I hold you very tenderly in my arms the three of you.

Ch Sch[..]

Translation notes:

Poor apples: the correspondent’s wife put apples in her parcel with the trench coat and they will get a bit rotten if the parcel does not arrive soon!

Dragées: usually sugar coated almonds offered for special celebrations such as birthdays, first communion and marriages.

Middle position: means no mild position only hard feelings

Vaguemestre: official title of the officer who collects and deliver letters in the army - also used in the navy

Comments:

“Concerning your thoughts inspired by the sermon AE Schimann, they are right. At the moment no middle position, either fanatic or fatalist. No space for anything else.” Schimann is most certainly a preacher but no information could be found on this person. He might be a high ranking clergyman or simply the local priest administering the parish where Mrs Schnurr (the wife of the correspondent) lives. Remarkably few sermons from the period have been preserved and if they have, they are difficult to access. The position of the Church during the war was probably as diverse as the sermons delivered by individual priests. Whilst many people went to Church in search of comfort and consolation, many priests also delivered patriotic sermons that amalgamated both the state rhetoric of love for the homeland and the Christian rhetoric of self-sacrifice and salvation. Push to the extreme this could lead to very harsh positions like that of the bishop of London Arthur Winnington-Ingramin in his Lent sermon of 1915 where he described the war duty as “a great crusade to kill Germans”. He justified killing as being “for the sake of the world” and encouraged the killing of all Germans, young and old. This is a position that our correspondent would probably have qualified as “fanatic” and that did not shock at the time. The British press for example did not comment on the sermon of the bishop of London when it was delivered. In both England and France, Christian rhetoric happily absorbed the language of patriotism and vice-versa without any feelings of paradox. It was only several years later that the Anglican Church felt compelled to disapprove the expression of such hatred. This reflected the position of a particular individual and not that of the Anglican Church as a whole. At the other end of the spectrum, the Archbishop of York stressed the links between the British and German royal families (sermon of November 1914). Such comments no doubt would not have been popular with the crowds.

More fatalist views were also expressed and it was not unusual for some French people to see the war as a sort of punishment. Many for example thought that the French law of 9 December 1905 that sanctioned the official separation of State and Church had brought God’s wrath. This had soured the relations with the Catholic Church as financial support was withdrawn and inventories led to disputes and bitterness.

War is never an easy issue for the Church to deal with. Whilst the papacy, from the very beginning of the war, made repeated appeals to peace and reconciliation, many felt that Rome was unsupportive and even suspected the Pope of secretly supporting the enemy. Local priests had the difficult tasks, in their sermons, of serving both their country and their religion. The soldier in this letter provides his wife with a very lucid analysis of the situation faced by the Church: in the face of immediate danger there is no space for philosophical debates but there can only be harsh positions.

Champagne campaign of September-October 1915